Return of the King: Part One

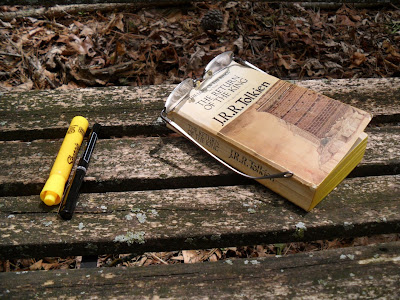

The cover of The Return of the King with all my necessary reading accessories sitting on the bench in my woods as I started rereading it a few weeks ago.

Note: This is part four of an overview to my recent, ninth reading of Tolkien’s classic fantasy. Whereas I have previously finished each volume in one post this time I am running much longer than I anticipated so I am posting it in two separate short essays. I'll finish this up in a few days.

The narrative remains split well into The Return of the King (ROTK). Frodo and Sam do not make an appearance for the first 200-plus pages. The last the reader knows of them is that Frodo has been taken prisoner by Orcs and Sam, heavily fatigued, follows toward the Tower of Cirith Ungol, carrying the Ring.

At this point Tolkien diverts the reader’s attention away from the main task of destroying the Ring by overwhelming us with action-packed details of the multifaceted build-up to the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, the largest battle of the trilogy and, indeed, of the entire Third Age. All our other characters are busy, in separate groupings, preparing for battle against the forces unleashed by Sauron at Minas Morgul near the end of The Two Towers.

After the battle, Tolkien gives the reader one of the story’s big pay-offs for unconventionally choosing to split the narrative and the resulting loss of contact with Frodo and Sam. To distract Sauron’s attention away from Mordor, our heroes and their little army gather, vastly outnumbered, before the Black Gate; taunting Sauron himself. Sauron can no longer take physical form (see The Silmarillion for why this is the case) so the Dark Lord sends the Mouth of Sauron out of the Gate to greet Gandalf, Aragorn, Pippin, Legolas, Gimli, and the other Captains. The Mouth brings tokens that deeply disturb the reader, because the reader has no idea at this point what has happened to the two hobbits who ventured with the Ring into Cirith Ungol.

I recall this was a powerful moment for me when I first read it, not yet knowing the story in full. I still think it is a fine example of Tolkien’s brilliance as a writer. The Mouth of Sauron proclaims: “’I have tokens that I was bidden to show thee – to thee in especial, if thou shouldst dare to come.’ He signed one of the guards, and he came forward bearing a bundle swathed in black cloths. The Messenger put these aside, and there to the wonder and dismay of all the Captains he held up first a short sword such as Sam had carried, and next a grey cloak with an elven-brooch, and last the coat of mithril-mail that Frodo had worn wrapped in his tattered garments. A blackness came before their eyes, and it seemed to them in a moment of silence that the world stood still, but their hearts were dead and their last hope gone.” (page 203) Since we know nothing of the fate of the two hobbits at this point, as readers we can fully relate to the emotional experience of the major characters at this moment.

But, Sauron is being cocky and it is all bluff. In fact, he has been intensely troubled for some time. This, of course, is not revealed until we get to the other half of the narrative. As Frodo and Sam are muddling toward Mount Doom Tolkien writes: “The Dark Power was deep in thought, and the Eye turned inward, pondering tidings of doubt and danger: a bright sword, a stern and kingly face it saw, and for awhile it gave little thought to other things; and all its stronghold, gate on gate, and tower on tower, was wrapped in a brooding gloom.” (page 245)

To me, this is another remarkable literary moment. Sauron is in gloom. The primary adversary in the narrative is actually doubtful and in despair. This is where evil touches goodness and this is where evil can leverage things, according to Tolkien. Tolkien’s sense of evil throughout The Lord of the Rings (LOTR) and The Silmarillion is curiously touchable. Evil is not just blatant terror and wickedness. It seems partly fair and innocent and even pitiable. It is upon these qualities that Tolkien’s harbingers of evil spin their subtle lies. It is all about the marketing spin and Sauron (like Morgoth before him) is great at spinning the facts in his favor.

The instrument of Sauron’s gloom is the same as that of Denethor’s despair. As mentioned in a previous post, the palantri give the story great depth even if they are not fully explained in the narrative. Specifically, they connect LOTR with the greatness that was Númenor in the Second Age and even further back than that to Valinor itself. Through a palantir Sauron has revealed to Denethor the overwhelming strength he has amassed both in Mordor and from allies to the south and east. Sauron poisons the disgruntled mind of Denethor.

Meanwhile, Sauron’s palantir has affected him. The Eye has seen Pippin in it (Sauron knows from torturing Gollum earlier in LOTR that a hobbit has the Ring). Then the Eye beholds Aragorn in a bold test of wills. Seeing these, for the first time in the story, the Eye turns inward. Sauron failed to control either Aragorn or Pippin the way he mastered Denethor (weakened by the death of his first son) and Saruman (weakened by the wizard’s greed for power). Sauron ponders the possibility that Aragorn has taken the Ring. Sauron expects the Ring to be used against him.

There is a second significance to the Eye turning inward. Sauron becomes pensive as the wind changes. This is marvelous minor thread in the narrative is worth noting. In the superb passage that includes the introspective Eye quoted above, Tolkien notes in the previous paragraph: “The wind from the world now blew from the West.” (page 245)

This changing of the wind is announced twice before. Sam acknowledges it to Frodo on page 240. Mordor had belched forth dark clouds over Osgiliath toward Minas Tirith as Sauron attacked. With the change of wind, however, the clouds are being pushed back over Mordor and even there a bit of light starts of defuse into the bleakness of Gorgoroth.

The second mention of the wind comes through the fascinating minor character of Ghân-buri-Ghân, chieftain of the Woses, the so-called “Wild Men of the Drúedain Forest,” who helps to guide the Rohirrim as they ride in mass to the aid of Minas Tirith. Tolkien describes his abrupt parting from the company of King Theoden: “But suddenly he stood looking up like some startled woodland animal snuffling a strange air. A light came to his eyes. ‘Wind is changing!’ he cried, and with that, in a twinkling as it seemed, he and his fellows had vanished into the glooms, never to be seen by any Rider of Rohan again.” (page 133)

The Eye of Sauron turns inward, contemplating (incorrectly as it turns out) what the palantir has told him, before the huge battle actually starts. In fact, Tolkien leads us to believe that it is primarily because of what Sauron sees in the stone that he launches his massive attack. “I spoke no word to him, and in the end I wrenched the Stone to my own will. That alone he will find hard to endure. And he beheld me.” (page 62) “For I showed the blade re-forged to him. He is not so mighty yet as he is above fear; nay, doubt gnaws him.’ ‘But he welds great dominion, nonetheless,’ said Gimli; ‘and now he will strike more swiftly.’ ‘The hasty stroke goes oft astray,’ said Aragorn.” (page 63)

Sauron is actually suffering from acute uncertainty and, indeed, fear. While he has vast forces and launches a grand assault, he is nevertheless gloomy and afraid. This is the state of weakness that allows the Ring to slip all the way to Mount Doom unnoticed. First, the Eye is not watchful but reflective. Then, the Eye returns its gaze outward as Aragorn and his strong but small army marches to the Black Gate. Sauron is more concerned with the returning King’s actions than with sensing the Ring in his backdoor. The whole climax of the trilogy depends on this.

Like so much of the trilogy, this is a rather risky and unconventional approach. Traditionally, a writer is supposed to veil their adversary in mystery and strength, yet Tolkien does not choose this path and in not doing so he risks the possibility that the story’s climax will lack punch and fail measure up to the tension created by the great Battle of the Pelennor Fields. Yet, as with everything else, Tolkien maintains the tension precisely because the fate of the Ring itself remains unknown to the reader until some 275 pages or so into ROTK.

Did Tolkien intend the wind changing from east to west to be a result of the Eye turning inward? I don’t know but it is an interesting aspect of the trilogy to discuss. Some Tolkien scholars believe that the changing of the wind is actually the work of Manwë, a Valar who was ever the greatest challenger of Morgoth. Ultimately, Manwë thrust Morgoth into the Void. There is little evidence to support this in LOTR itself, however, as Manwë is never mentioned in ROTK. Yet, some scholars think that the overseeing force of the Valar is implied by Tolkien. And Manwë is “the lord of the air and the wind.”

The smudge of red in the lower left corner is the flame from Mount Doom as seen from Barad-hur on the cover of my 1975 paperback edition, which has survived nine readings and other times of scanning and study. Cover painting is by Tolkien himself.

Comments