Sherman and Hood: A Battle of Letters

|

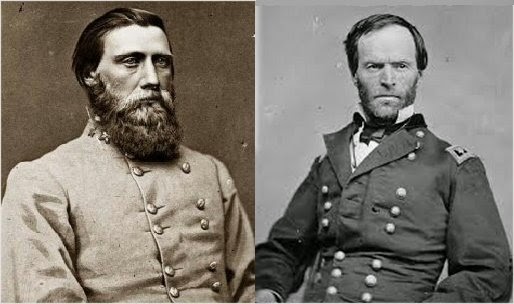

| Generals John Bell Hood and William Tecumseh Sherman. |

So an interesting affair is introduced by General William T. Sherman in his memoirs. He would later burn much of Atlanta but before that he occupied it in an aggressive military manner. Sherman cleared Atlanta of all civilians. The elderly, sick, crippled, women, and children were all without exception ordered from their homes. He saw this action as necessary and logical. His Confederate opponent, General John Bell Hood, took great exception to Sherman's handling of the civilian population and used the occasion to exchange letters with Sherman in a war of words over the merits of Sherman's action within the context of "the rules of conduct in war", which greatly aggravated Hood's southern sense of honor, though, as Sherman points out in the exchange, the southerners carry plenty of aggressive war guilt as well. (The importance of guilt in the reconciliation of southerners to their own catastrophic defeat is well-addressed in Why The South Lost The Civil War, 1986).

Both men included the exchange of correspondence in their respective memoirs. Sherman used the matter to routinely close the section of his memoirs detailing the campaign for Atlanta. Hood, however, wished to emphasize the matter and devoted an entire chapter to just these letters under the title "Correspondence with Sherman - Citation on the Rules of War." It should be noted that both men respected each other after the war and Hood was Sherman's guest on several occasions.

In their respective remembrances, both men agree that the matter began with an exchange of prisoners. 2,000 Confederates would be exchanged for 2,000 Yankees, mostly from the infamous prison at Andersonville. Hood knew that the Yankees would not have had time to ship northward all the prisoners captured during his three disastrous attacks in late July. Sherman knew the situation at Andersonville was likely desperate. The prisoner exchange took place in mid-September but on its coat tails was something Sherman completely controlled.

Sherman's initial letter to Hood is dated September 7, 1864. It is brief and to the point. Without attempting to explain his reasoning to his adversary he simply states that he his clearing Atlanta of all civilians and giving each citizen a choice. They can go north, where his armies and rails would provide for them up into Tennessee or Kentucky if they wish to travel that far. Or they can go south. In which case Sherman would provide rail transportation as far south as the rails were in good repair, within about 15 miles of Hood's army. From there Hood must arrange to carry the thousands of them by whatever wagons he can find to Lovejoy Station where they can be transported as they like further south or east by Confederate trains.

To Hood this is not only an ultimatum but it is an outrage as he will be forced to use his own supply wagons, needed for his own army, in order to accommodate this mass exodus. Hood can barely feed his own army yet he will be temporarily burdened with thousands more mouths to feed. And the outright ordering of women and children from their homes is an affront to Hood's sense of honor. So, after finally realizing he has no choice in the matter, two days later, on September 9, Hood fires off a short letter of protest ending with: "And now, sir, permit me to say that the unprecedented measure you propose transcends, in studied and ingenious cruelty, all acts ever before brought to my attention in the dark history of war....In the name of God and humanity, I protest, believing that you will find you are expelling from their homes and firesides the wives and children of a brave people." (page 230)

Sherman's reply came quickly on the next day, September 10. It is much more lengthy than his first letter, which was only a few paragraphs. This letter amounts to one and a half pages as published in his memoir. It begins in the high style of the period recognized and used by both generals. "I have the honor to acknowledge receipt of your letter...consenting to the arrangements I had proposed to facilitate the removal south of the people of Atlanta, who prefer to go in that direction. I enclosed you a copy of my orders, which will, I am satisfied, accomplish my purpose perfectly." (pp. 593-594) Sherman the proceeds to take exception to Hood's characterization of his campaign as "unprecedented." He picks apart Hood's philosophical appraisal of his campaign and compares it as similar with the behavior of Confederate armies in recent operations.

Sherman's boldest contention is: "You defended Atlanta on a line so close to the town that every canon-shot and many musket-shots from our lone of investment, that overshot their mark, went into the habitations of women and children. General Hardee did the same at Jonesboro', and General Johnston did the same, last summer, at Jackson, Mississippi. I have not accused you of heartless cruelty, but merely instance these cases of very recent occurrence, and could go on and enumerate hundreds of others, and challenge any fair man to judge which of us has the heart of pity for families of a 'brave people.'" (page 594)

But ultimately his letter gets around to Hood's plea to God. "In the name of common sense, I ask you not to appeal to a just God in such a sacrilegious manner. You who, in the midst of peace and prosperity, have plunged a nation into war - dark and cruel war - who dared and badgered us into battle, insulted our flag, seized our arsenals and forts that were committed by the (to you) hated Lincoln Government; tried to force Kentucky and Missouri into rebellion, in spite of themselves; falsified the vote in Louisiana; turned your privateers to plunder unarmed ships; expelled Union families by the thousands, burned their houses, and declared, by an act of your Congress, the confiscation of all debts due Northern men for goods had and received!...if we must be enemies, let us be men, and fight it out as we propose to do, and not deal in such hypocritical appeals to God and humanity. God will judge us in due time, and he will pronounce whether it be more humane to fight with a town full of women and families of a brave people at our back, or to remove them on time to places of safety among our own friends and people. I am, very respectfully, your obedient servant." (pp. 594-595)

Once again it takes Hood two days to respond. His letter of September 12 is the longest of the exchange, twice the length of Sherman's previous missive, which inspired it. Hood begins by stating that had Sherman not gone such great lengths in his letter to justify what Hood terms "an act of barbarous cruelty" he would have been contented to close the matter. However, "you have chosen to indulge in statements which I feel compelled to notice, at least so far as to signify my dissent, and not allow silence in regard to them to be construed as acquiescence." (page 232). Hood then proceeds, in great detail, to take exception with every point made by Sherman.

"I feel no other emotion other than pain in reading the portion of your letter which attempts to justify your shelling Atlanta, without notice, under the pretense that I defended Atlanta upon a line so close to town that every cannon shot, and many musket balls from your line of investment, that overshot their mark, went into habitations of women and children. I made no complaint of your firing into Atlanta in any way you thought proper. I make none now, but there are a hundred thousand witnesses that you fired into the habitations of women and children for weeks, firing far above and miles beyond my line of defense. I have too good an opinion, founded upon observation and experience, of the skills of your artillerists, to credit the insinuation that they for weeks unintentionally fired too high for my modest field works, and slaughtered women and children by accident or want of skill." (page 233)

Hood rebuts Sherman's points (what he terms "the residue of your letter") on such matters as responsibility for the war, actions taken early in the war, the status of Kentucky, Missouri, and Louisiana, naval matters, and the economic consequences of the war for northern merchants. He continues: "You order into exile the whole population of a city; drive men, women, and children from their homes at the point of bayonet, under the plea that it is in the interest of your Government...You issue a sweeping edict, covering all the inhabitants of a city, and add insult to the injury heaped upon the defenseless by assuming that you have done them a kindness...And, because I characterize what you call a kindness as being real cruelty, you presume to sit in judgment between me and my God; You came into our country with your Army, avowedly for the purpose of subjugating free white men, women, and children, and not only intend to rule them, but make negroes your allies, and desire to place us over an inferior race, which we have raised from barbarism to its present condition, which is the highest ever attained by that race, in any country, in all time." (page 235) Of course, this exchange would not be the complete representation of the period that it is if it did not contain racist comments, which were one of the reasons for the war to begin with.

Here is the final letter penned by Sherman, the shortest of all letters considered here, in its entirety so that you can see the complete formal style of such correspondence as we are considering. It was written two days later:

"Headquarters Military Division of the Mississippi, In the Field, Atlanta, Georgia, September 14, 1864

"General J.B. Hood, commanding Army of Tennessee, Confederate Army

"General: Yours of September 12th is received, and has been carefully perused. I agree with you that this discussion by two soldiers is out of place and profitless; but you must admit that you began the controversy by characterizing an official act of mine in unfair and improper terms. I reiterate my former answer, and to the only contained in your rejoinder add: We have no 'negro allies' in this army; not a single negro soldier left Chattanooga with this army, or is with it now. There are a few guarding Chattanooga, which General Steedman sent at one time to drive Wheeler out of Dalton.

"I was not bound by the laws of war to give notice of the shelling of Atlanta, a 'fortified town, with magazines, arsenals, foundries, and public stores;' you were bound to take notice. See the books.

"This is the conclusion of our correspondence, which I did not begin, and terminate with satisfaction. I am, with respect, your obedient servant,

W.T. Sherman, Major-General commanding" (page 602)

In his memoirs, which were published after Sherman's, Hood offers a commentary on the nature of the discussion between the two generals. Hood admits he was tempted to respond to Sherman's curt "see the books" comment. He then proceeds to argue "that General Sherman's conduct, in this instance, was in violation of the laws which should govern nations in time of war." He cites examples of military conduct during the Peninsular War in addition to numerous passages from three war scholars on the nature of "unnecessary violence" and on the protection of non-combatants in populated areas, implying again that Sherman's orders were "barbarous cruelty."

Compared to Hood, Sherman's memoirs make no comment on the affair. He merely collects the letters and presents them for the reader's consideration as if they speak for themselves. However, Sherman includes some correspondence that Hood does not. Both memoirs reprint the plea by two City Councilmen and the Mayor, James M. Calhoun, addressed to Sherman asking that he reconsider his eviction orders. Sherman pens a very lengthy reply to these gentleman, as long as anything he wrote to Hood. Nothing better documents Sherman's perspective and this serves as comment enough to compare with Hood's analysis. In part it reads:

"You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices today than any of you to secure the peace. But you cannot have peace and a division of our country....You might as well appeal against a thunderstorm as against these terrible hardships of war. They are inevitable, and the only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home, is to stop this war, which can only be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetrated in pride." (page 601)

Sherman gathered all this correspondence with Hood and with the Mayor of Atlanta and sent it to Washington for review by Army Chief of Staff Major-General H. W. Halleck. Sherman concludes this matter in his memoirs by simply publishing Halleck's reply dated September 28. Halleck writes:

"Not only are you justified by the laws and usages of war in removing these people, but I think it was your duty to your own army to do so. Moreover, I am fully of the opinion that the nature of your position, the character of the war, the conduct of the enemy (and especially of non-combatants and women of the territory which we have heretofore conquered and occupied), will justify you in gathering up all the forage and provisions which your army may require, both for a siege of Atlanta and for your supply in your march further into the enemy's country. Let the disloyal families of the country, thus stripped, go to their husbands, fathers, and natural protectors, in the rebel ranks; we have tried three years of council action and kindness without any reciprocation; on the contrary, those thus treated have acted as spies and guerrillas in our rear and within our lines." (page 603)

Each side exchanged 2,000 prisoners, Atlanta was evacuated of all civilians, most choosing to go south, placing the burden for the exodus upon Hood, and Sherman militarized the city for several weeks. Sherman was unclear as to what his next move should be. But Halleck's passing suggestion that he "match further into the enemy's country" would soon be realized in Sherman's infamous "March to the Sea." Much of Atlanta would be burned to the ground, clearly destroying the homes of the evicted southerners, something beyond Sherman's stated intent in these letters. Thus the rules of war would be shown to be, as they have for all history, strictly the interpretation of the victor. (In fairness, it should be pointed out that Confederate forces burned the Pennsylvanian town of Chambersburg on July 30, 1864.)

This battle of letters between Sherman and Hood could well represent the first clash of histories of the war. Which is more historically accurate? Sherman pointing out the great Southern responsibility for all the hardships of the war? Or Hood believing that the South was victimized, its culture insulted and threatened by a hostile North. My guess is there is more than a bit of truth (and propaganda) in both perspectives. These letters contain a wealth of contemporary perspective and it is valuable to consider them when researching and debating the nature of America's bloodiest war.

Note: Sherman sent his final letter to Hood 150 years ago today.

Comments