Gaming Barbarossa

|

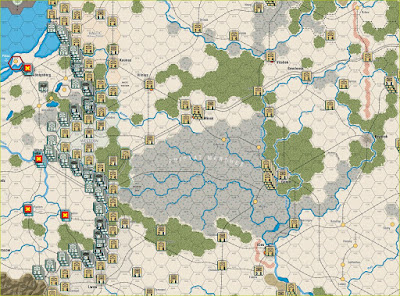

| The opening situation for Operation Barbarossa, June 22, 1941. The Germans are massed along the border. The vastness of the Soviet Union and the restructuring Soviet military is before them. The Pripyat Marshes are the dominant feature on the map. |

On this day two of the largest military operations in history began on the Eastern Front. Operation Barbarossa started on June 22, 1941, the overly ambitious attempt by Nazi Germany to conquer and basically annihilate the Soviet Union west of the Ural Mountains. Three years later, June 22, 1944, Operation Bagration unleashed an offensive force unmatched in history and destroyed the German Army Group Center, handing Hitler the worst military defeat in German history and paving the way for the conquest of Germany all the way to Berlin.

The Dark Valley was recently republished by GMT Games in a “deluxe” edition, which I purchased having already played the original game when it came out back in 2013. This major “upgrade” corrects some rules issues and counter art. Generally, the printing of all components is improved with a mounted map and map art being completely revised into something more aesthetically pleasing than the original. It was perfect timing for a game I have always enjoyed on a subject matter I find fascinating. I am now playing it through. As I have another wargame still on my gaming table, I decided to play this one in its cyberboard format.

I chose the Barbarossa scenario of the game for this summer. The Dark Valley also allows you to play the situation at the beginning of the 1942 and 1943 campaigns, in addition to Bagration in 1944. I have played Bagration before and am thinking about tackling it next summer, but we’ll see. For this summer and fall, I will play through 1941 and see how far I get. So, I’ll blog a bit about the history and the game from time to time as I play.

I have a little over three shelves of books on the Eastern Front in my library. That’s in addition to a couple of shelves of books on other topics of World War Two. Most of them are either biographies of various generals on both sides, or they are general histories of the war on that front, a few deal with specific units that fought in the war, or they deal with campaigns other than the two I mentioned above.

Six books in particular merit a mention as I begin my play of Barbarossa. David Glantz might be the foremost American historian of the war, having been granted access to materials in the former Soviet Union that were not available in the 1980’s and 1990’s when I started to become obsessed with this topic. His Barbarossa: Hitler’s Invasion of Russia 1941 was published in 2001 and is the best overall single volume I’ve found on the campaign. In 1993, Glantz published The Initial Period of War on the Eastern Front 22 June – August 1941 which goes into great detail about the fighting covered in the first few turns of The Dark Valley. Glantz also published Stumbling Colossus: The Red Army on the Eve of World War in 1998, which deals with Soviet preparations (or lack thereof) for war with Germany.

Other than Glantz, there is another excellent book on the first year of the Russian Front entitled War of Annihilation: Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front 1941 by Geoffrey P. Megargee. This work is more sociological than military. Although there are some details about combat, it mostly has to do with how official Nazi policy evolved and was (literally) executed during the German invasion. You can find some gruesome details in this one that aren’t available in purely military histories.

The 1952 memoir of German panzer General Heinz Guderian is interesting, if self-serving, to understand some of the complexities of the German invasion in 1941. Likewise, Otto Preston Chaney’s Zhukov biography (revised 1996) gives a splendid account of all the issues the Soviet’s were attempting to address in 1941. Finally, Thunder on the Dnepr (TotD) (2001) is a “fringe” history that affords a lot of interesting details facing the Soviet Union before and during the 1941 campaign.

Collectively, these offer a variety of perspectives on the part of the war I am attempting to game. For this blog post, I want to focus on the Soviet preparations and controversies on the eve of Hitler’s maniacal quest for Lebensraum.

Ever wary of a possible military overthrow of his communist regime, Joseph Stalin purged the Soviet military of many well-trained marshals and mid-level commanders beginning in 1937. At the time Hitler invaded, the Soviets had not fully reorganized themselves, partly due to the staggering number of officers Stalin had ordered either shot or imprisoned, and partly due to an internal conflict among his remaining commanders over strategy.

One school of thought, best advocated by General P. G. Pavlov, was that the Soviets should rely upon massed mechanized units and their superior tank designs (T34’s and KV1’s were better than any German tanks in 1941, though they were not yet plentiful) to counterattack any assault coming from the west as close to the frontier with Germany as possible. Such attacks, it was believed, would destroy the German offensive before it started and serve as a springboard for a counter-invasion by the Soviets into Greater Germany.

But Marshal S. K. Timoshenko and General Georgy Zhukov disagreed. They felt that it would be better to absorb the might of the German onslaught, wearing it down bit by bit, and then destroy it with counterattacks once the Germans extended themselves far enough to expose their flanks. The Soviet military conducted two war games in January 1941, where Pavlov and Zhukov faced each other. Each played one side then they switched commanders to take the other side. Zhukov defeated Pavlov both times, thereby catching Stalin’s eye and ear.

What happened next is a matter of controversy. According to TotD, a third wargame was secretly held in February. Pavlov and generals supporting him were not told about this game. Only Timoshenko, Zhukov and their supporters participated. This game tested the strategy of giving ground in order to destroy the German forces later. The authors offer a copy of the invitation to the secret third game as evidence. Supposedly, this game convinced Stalin that the anti-Pavlov contingent had a superior strategy.

There are some problems with this theory, however. One of the primary ones is that on May 15, 1941 Zhukov actually recommended that Stalin consider a pre-emptive attack on the Germans. Stalin disregarded this as he did not want to do anything that might provoke the Germans. He still felt that Hitler would not attack him. When asked about the massing of German troops along the Soviet border, Hitler simply responded that he had to redeploy his army to avoid British bombers in other parts of the Third Reich.

Obviously, if Zhukov was thinking of a pre-emptive strike this would contradict the idea that he had a “secret” plan to destroy the invaders further within the Soviet Union. According to TotD this was a clever ploy on the part of Zhukov to mislead Pavlov about the true change in Soviet strategic thinking. Frankly, I find this difficult to believe.

Why would Stalin try to “trick” Pavlov or anyone else when he was perfectly accustomed to having any one shot if they didn’t go along with his thinking? (Stalin ended up ordering Pavlov shot anyway for his failure to turn back the German assault.) It seems to me far more likely that Zhukov simply became alarmed by intelligence reports and altered his thinking. If there ever was an elaborate plan to “fake” the Germans to drive deep into Russia, it was probably discarded with the changing military situation.

TotD concludes that the 1941 campaign played out just the way Timoshenko and Zhukov wanted it to. Despite many mistakes and almosts, the deteriorating situation was actually worse on the Germans than the Soviets and the massive counterattack by the Russians in the Battle of Moscow ended up more or less the way the Soviet leaders wanted it to. I don’t buy it. There were too many close calls, unplanned by the Soviets, that could have gone either way, despite the massive encirclement of millions of Soviet troops, before Barbarossa was decided as a German defeat. Zhukov was good but he was also lucky.

Instead of careful, virtually prognostic planning by the Soviets, David Glantz, in his more reasoned and thoughtful analysis, writes that the Soviets were more culturally stable and economically established than Hitler wanted to admit. The Russian military, even if qualitatively inferior to the Germans, was capable and tenacious. The August 1941 decision by the Germans to temporarily shift their emphasis from the capture of Moscow to the conquest of the Ukraine cost them their chance take the Soviet capital. (TotD says this was foreseen and planned for by Timoshenko-Zhukov.) The Germans did not have the logistical infrastructure to keep their panzers fully supplied and operational in such an enormous expanse over a long period of time. The Russian climate and terrain proved to be more difficult than the Germans planned for.

Finally, regarding the capture of Moscow, Glantz states: “The end of June start time, in conjunction with the time lost during the battle of Kiev, took bitter revenge upon the Germans. If the incorrect decision of August 1941 were not made, the time left before the beginning of the mud period would have been sufficient for decisive success. However, it would still have been very close.” (Barbarossa, page 212)

It is precisely close, complex military situations like this that I enjoy gaming. So, back to The Dark Valley, it is June 22, 1941. The invasion begins.

This game has a ‘chit-pull’ mechanic, meaning, instead of a move and combat phase by one side and then the other, a series of ‘action chits’ are randomly drawn out of a cup to indicate what to do next in the flow of play. I really like chit-pull wargame systems because they are terrific for solitaire play. What happens next is always a surprise. The entire game is 44 turns long, each turn taking up one month of historical time, with some special considerations for Turn One as it represents only the last 8 days in June.

To begin with the Soviet army is weak though plentiful. There are a lot of units to be killed and far more that will show up later as reinforcements. The Germans, by contrast, are at the peak of their power. Though they will gain several very powerful units later as reinforcements, they will never be as strong, overall, as they are at the beginning of the game.

While the Germans are masters of mobility and dance around almost at will, the Soviets are slower and are forced to counterattack due to mandates by Stalin at frequently unfavorable odds. This gives the illusion of weakening them even further. And, in a sense, this isn’t an illusion. Large swaths of troops and territory will be lost in the initial German drive. But, at the same time, the Germans grow weaker every time they get an “Exchange” result in combat, forcing them to lose steps of their units. Sure the Russian losses are FAR worse, but they will ultimately be replaced (unless the Germans win quickly) while the German losses eventually outstrip their ability to replace them.

It might seem the Soviets have nothing to do in Turn One. But careful placement of their units can make the Germans work a lot harder. Also, the mandated counterattacks allow for the Soviets to move and attack as they see fit, which usually sets up some 1-1 odds. These are not the best odds but the game’s combat results table favors causalities by both attacker and defender. Even at the highest 6-1 odds, for example, there is still a 1/6 chance the attacker will lose a step. That goes to a 1/3 chance for 5-1 attacks.

To broaden the perspective, at 1-1 odds there is a 1/3 chance the attacker will cause a step loss for the defender. So, the Soviet counterattacks early in the game can inflict step losses on the German, if he can manage enough attacks. They are certainly reckless in wargame terms, but they can be somewhat effective. Bottom line: The German will lose several steps during the initial turn from their own attacks and from Soviet counterattacks, so the Soviets actually have a lot to do, even though they will get their butts kicked as far as territory control.

|

| The isolation of Minsk my Army Group Center. Approaching Smolensk. |

For Game Turn One in my play, the Soviets lost a total of 27 steps. Germans lost 7. I report on the progress of the game in future posts.

Comments