A Look at War and Peace: Volume One

|

| My kindle cover. |

Note: Page numbers and quotes are from the modern translation.

It's been a dozen years since I last read Leo Tolstoy's towering achievement, War and Peace. It is certainly one of my all-time favorite novels. I read it maybe a couple of times as a philosophical and spiritual work before I went to India. It was also a plus in that it deals with the Napoleonic Wars, which is another of my lifelong military history interests, This is only the third or fourth time I've read the novel but I was better acquainted with the narrative on this tour of the novel than I was when I reread it in 2010. This time, anticipating my New Year's resolution, I began reading it after Thanksgiving and finished it in late January. It is the longest single-volume novel I have ever read and covering it in about nine weeks is a leisurely but focused pace. Then I sat the novel aside to let it peculate in the back of my mind.

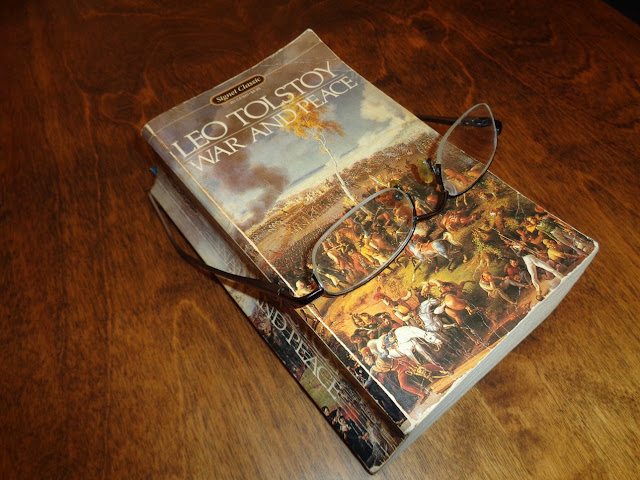

|

| My 1980 paperback. |

All my previous readings were from an old paperback (the very one I bought in college) containing a translation by Ann Dunnigan. This time I thought I'd try a newer translation just to see what I thought. After some research I chose the one by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. They seem to be the favorites among people more versed in translations than myself, though preferences vary among several translators.

To be honest, I am not overly impressed with Pevear/Volokhonsky. I'm sure in many ways it is a more faithful rendering of the Russian. Dunnigan has General Kutuzov addressed as “Your Highness” in her version while the more modern translation uses “Your Serenity” which I suppose is more accurate, certainly less generic. P/V also chose to leave the numerous sections where characters speak French written in that language instead of offering them in English.

I had no idea Tolstoy used so much French in his original manuscript. That was surprising and interesting but, nevertheless, as a mater of convenience, I prefer Dunnigan's translation of the vast majority of the French (except for a few exclamations and routine phrases) into English. On the other hand, reading her version is the reason why I never realized so much of the novel is in French to begin with. P/V offers all the French translated into English, of course, but you have to check the footnotes for each section of the novel to get that.

Scanning through my old paperback as I read the P/V version, comparing certain sections along the way, I discovered that much of the phrasing and word choices were more to my taste in my original paperback version, though, once again, I'm sure P/V is technically more accurate. There were a few noteworthy sections where the newer version was more poetic, sometimes surprisingly so. I'm glad I read it.

I bought the P/V translation for my kindle app. That offers certain advantages. It simplifies searching the massive narrative, compared with thumbing through the 1450 pages of my paperback to locate a particular paragraph. It also means I don't have to devote more of my precious dwindling book shelf space to another massive physical book. Moreover, it makes it far easier to quote from the work. I can simply copy and paste instead if retyping quote-worthy passages from my old paperback.

Also, I enjoyed reading the novel in a “clean” environment, without my previous marks and marginalia. It was surprising that I often unknowingly made my new highlighting in passages that caught my eye in my previous readings. As always, however, I discovered exciting new things with this reading that I had not noticed before.

My hope is to give a series of posts that will serve as an broad overview to the novel. My aim is to follow my three favorite characters through the narrative: Prince Andrei, Natasha, and Pierre. Napoleon and Kutuzov will also make an appearance, as you will soon see. I will leave out the vast bulk of Tolstoy's characters (there are over 500 throughout the course of the work) for the sake of brevity but absolutely essential ones will necessarily be included for this overview to make sense.

Volume One of the novel (“Book” One in Dunnigan) is chiefly about war but it introduces all the main characters while featuring a couple of balls as well as other glimpses of social life in Moscow at the dawn of the Napoleonic Wars (early 19th century). Napoleon himself is the topic of conversation as the narrative begins.

Pierre and Prince Andrei are discussing “Bonaparte” at an aristocratic social gathering. Pierre admires Napoleon. He considers that the Emperor mastered the revolution in France, making the right decisions and shaping it into something beneficial to the French and possibly the world. Prince Andrei is supportive up to a point. He too admires Napoleon but has reservations about some of his actions and what it might mean for Russia. He wants Russia to remain as it is and not be impacted by the French affairs despite his admiration.

Pierre is rather bumbling and uncouth, “fat” (the P/V term) and prone to absentmindedness. He means well but he has no real concept of how he is perceived by others and he misinterprets standard decorum and basic intentions which makes him socially awkward. He is concerned with great philosophical matters and has some degree of common sense but he is inexperienced and out of place in his own element. His head is in the clouds.

We first meet Napoleon's Russian adversary, General Kutuzov, in a review of his troops after the long march from Russia to begin what would be the Ulm Campaign. He desires to see the troops in the worst possible condition because he wants to know their true status after such an arduous march and to impress upon the Austrian commander that the Russians need a rest. The battalion commanders, however, independently decide everyone will be in parade dress. Some soldiers spend most of the night preparing their uniforms for the review.

Andrei is going to war because he considers his personal life to be “not for me." He has an unfulfilling marriage. He advises Pierre to marry only when he is old because "all that is good and lofty in you will be lost." He confides in Pierre that he has told no one else about how unhappy he is in his marriage. He feels imprisoned by it, though he has a fine wife. Tolstoy writes of Andrei that: “He used to say that there were only two sources of human vice: idleness and superstition; and that there were only two virtues: activity and intelligence.” (p. 87) This captures Andrei's character in a single sentence, though it omits his life crisis.

The first we learn of actual war is detailed on page 100. Prince Andrei explains the Russian strategy for the coming campaign against Napoleon to his harsh, overbearing, but caring father. They keep lapsing from speaking Russian into French, which cleverly accentuates the nature of the coming conflict, and the influence of the French language on basic aristocratic interaction. His father generally scoffs at the Russian plan (as he does with most things in life). Andrei attempts to say he doesn't necessarily approve of the plans but, in a recurring motif, he never actually gets to say what is on his mind.

The two have an interesting exchange about “Bonaparte” with his father calling him “lucky.” The novel stresses that, while Andrei objects to some of what his father is saying, he does not interrupt him and withholds his disagreements. It is obvious Andrei is frustrated not only by his marriage but by his father as well and his inability to be his authentic self.

Princess Marya gives her brother an icon to wear into battle. Andrei is not a religious person but he agrees to wear it simply to please and comfort his sister. She doesn't give it to him until he crosses himself in the Russian Orthodox manner and then kisses it in her hand. Only then does she let him take it. Andrei is a kind and patient man. Or so it seems. In reality he is a seething wreck of a soul and the most interesting character in the early stages of the novel. War is Andrei's means of escape from his life. He leaves his pregnant wife in the hands of his father, asking him to send for someone from Moscow (more highly trained) when she goes into labor. The old man scoffs and reluctantly agrees.

Meanwhile, Pierre enjoys a life of decadence and partying. In fact, he is a bit of a hell raiser. In one drunken escapade he ties a small bear to a policeman. He has failed to choose a career for himself and he was banished from Petersburg for his riotous behavior. He rather unexpectedly comes into his inheritance, as a bastard son, which shocks and upsets his father's family who begin the novel scheming what to do with wealth that ends up going to Pierre instead. He is initially generous, sometimes foolishly so.

Most immediately, his life takes on a more solitary quality, as he settles in to suddenly becoming a Count and living on his estate outside Moscow. Despite this, he is suddenly in demand for random visits because he is now a source of wealth that many people want a piece of. This places him in a “state of mildly and merry intoxication.” He meets Ellen at this time.

Or Hélène as she is, more accurately, translated by P/V. Tolstoy offers us a marvelous, titillating description of her sensual and erotic character. In fact he writes of Pierre specifically being aware that: “there’s something vile in the feeling she aroused in me, something forbidden. I’ve been told that her brother Anatole was in love with her and she with him, and there was a whole story, and that’s why Anatole was sent away.” (page 207) Anatole will appear again much later in Volume Two.

Any yet Pierre, as with his partying, can't control himself. Even though he realizes the hot woman has little intellectual capacity, which he constantly uses to talk himself out if it, he ends up marrying her after only six weeks. Their sexual relationship begins with a voluptuously described kiss. The passion is not the focus of the novel, however, and is understated, though clearly known. This is a case with Tolstoy and sex throughout the novel, conforming to the mores of his time, being acceptably scandalous by eluding to things not fully described. The novel is filled with such innuendo.

Natasha is introduced as "dark-eyed, big-mouthed, not beautiful but lively." She is also a talented singer. Her father calls her a "ball of fire." She is 12 and thinks she's in love with a boy named Boris. She wants him to kiss her and he promise to marry her in four years. She usually gets what she wants. She loves pineapple ice bream. She thinks Pierre is fat and funny. She loves to run to wherever she is going. She asks Pierre to dance with her at an early ball. Pierre doesn't know much about dancing and charmingly asks her to be his teacher. She is thrilled to be dancing with a “grown-up” who came from “abroad.” Pierre is Russian, of course, but has spent most of his youth up to this time in Europe. Even at 12, Natasha is already highly flirtatious.

She is also intuitive, highly attentive to how her family interacts and can spot nuances in the family dynamic with ease. She is gossipy and confides in Sonya, her cousin and best friend. There is comparatively little about her in Volume One because she has no understanding of war at all and is child-like compared with the other major characters at this stage of the narrative. It is worth noting, however, that she develops out of childhood into a vibrant adulthood through the course of the novel and the brief glimpses of her in childhood are useful to her amazing character arc.

A surprise occurs when Kutuzov welcomes an Austrian general, worn with combat and travel, to his headquarters. The general introduces himself as “the unfortunate Mack.” It is a shock to many of Kutuzov's staff. Mack was supposed to be defending Ulm from Napoleon but he met by disaster in a brilliant move by the French commander. Tolstoy abruptly exposes the reader to the extent of the loss by having Mack appear as a virtual nobody and become the disgraced symbol of a major military setback. Kutuzov is stoic in the face of this. Prince Andrei, one of Kutuzov's most trusted aides, listens as Mack tells his story and realizes the campaign is lost before Russia could even participate. Kutuzov will now retreat toward Vienna to seek a more favorable place to give battle.

That first battle, a skirmish really, takes place at an unnamed bridge. The Russians are burning bridges behind them to slow down the French advance. This is the first time the reader gets to experience Tolstoy's lively and detailed description of battle, capturing all the confusion that goes along with it through the various characters involved. One of these characters is Natasha's brother Nikolai Rostov. In his first taste of battle he hears a call for “stretchers!”, for example, but does not pause to understand what it means as he is part of the Russian countercharge.

Ultimately, the French bring up some artillery, hold their position and the Russians continue their retreat. Other minor skirmishes follow as the French dog the retreat. At one point the Russians drive them back and Prince Andrei takes some satisfaction in this but only briefly, before the weight of his responsibilities as a key member of Kutuzov's staff overtake him.

Tolstoy offers lengthy descriptions of the disarray in the ranks as the retreat continues. Wagons, artillery, cavalry, infantry are all competing for the same road space. We are introduced to Prince Bagration who tends to be bolder in his planning than Kutuzov. Bagration is ultimately entrusted with the rearguard detachment as the rest of the army continues to seek proper ground to offer a large battle. Prince Andrei begs Kutuzov to allow him to stay and assist Bagration but Kutuzov refuses. “I need good officers for myself,” he states, commanding Andrei to enter his carriage.

Tolstoy gives a fairly good overview of Kutuzov's strategic options and reasons for Kutuzov's decisions. But he also gives a good account of the “grunt” level too. Soldiers desiring vodka, their living conditions, the state of their uniforms and their minds does not escape at least a brief examination. One of the many things that makes War and Peace such a great novel is how much humanity Tolstoy works into his characters and the story. Nothing from the highest strategy to the lowest rumbling stomach escapes his gaze.

Then we come to the first proper battle in the novel, the Battle of Schöngrabern (page 177). Bagration's rearguard offers battle and Prince Andrei is there to assist. Tolstoy uses this character to describe the battle. It features a very important moment in the novel. Tolstoy writes about the commander of a Russian artillery battery shelling a nearby village, setting it ablaze because the French were concentrated there. The resulting fire creates disorder in the French ranks.

“No one had given Tushin any orders about where to shoot or with what, and, having consulted his sergeant major Zakharchenko, for whom he had great respect, he had decided that it would be good to set fire to the village.” (page 181) This is the first reflection we have of Tolstoy's version how history works. History is made not by the planning of the classically heroic but by hundreds and thousands of isolated individual decisions. It seems like a small detail to the reader at this point but this begins to set the stage for a full-blown philosophical examination later in the novel.

Then on the next page we get this: “Prince Andrei listened carefully to Prince Bagration’s exchanges with the commanders and to the orders he gave, and noticed, to his surprise, that no orders were given, and that Prince Bagration only tried to pretend that all that was done by necessity, chance, or the will of a particular commander, that it was all done, if not on his orders, then in accord with his intentions.” (page 182) A strong suggestion of Tolstoy's theory of history later on.

Ultimately, the Russians charge and rout the French. Then comes a truly brilliant passage in which Nikolai Rostov, awakens to find himself pinned by his dead horse and unable to orient himself as to which side of the line he is on. This detailed sense of battlefield disorientation is very affecting and wonderful to read. (pp. 188 - 189)

|

| Sample of text of Rostov mentioned above. |

But there is so much more than disorientation on the battlefield. “As a result of the dreadful rumbling, the noise, the necessity for attention and activity, Tushin did not experience the slightest unpleasant feeling of fear, and the thought that he could be killed or painfully wounded did not occur to him. On the contrary, he felt ever merrier and merrier. It seemed to him that the moment when he saw the enemy and fired the first shot was already very long ago, maybe even yesterday, and that the spot on the field where he stood was a long-familiar and dear place to him. Though he remembered everything, considered everything, did everything the best officer could do in his position, he was in a state similar to feverish delirium or to that of a drunken man.” (page 193) This passage is as Dostoevsky-like as Tolstoy gets.

Tushin's guns are withdrawn from French fire in the presence of Prince Andrei. Andrei commends Tushin's use of his personal initiative in front of Bagration, who thought he needlessly exposed his guns. Instead of rebuking Tushin, Bagration accepts Andrei's assessment dismisses the artillery officer. Andrei then turns his back on Tushin and walks away feeling dejected by the battle. “All this was so strange, so unlike what he hoped for.” (page 199) Even in small victories this man is haunted by the gnawing emptiness of his existence.

Before the Battle of Austerlitz, Nikolai, who literally worships the Tsar, is dressed in parade uniform with his cavalry battalion and being reviewed by Alexander himself. For two seconds their eyes meet. Rostov, as Tolstoy more often refers to him, is in awe when Alexander suddenly gallops away. Shortly thereafter a small battle takes place resulting in the capture of a French cavalry squadron. Afterward Rostov gets drunk with his comrades.

Then we come to Austerlitz, one of the greatest battles in western history. Kutuzov confides to Prince Andrei that he expects to be defeated. Andrei is not allowed to express his opinion (yet again) at the subsequent Russian council of war. In fact he does not know which of the various conflicting strategies is the best choice. The council leaves him with “a vague and disturbing impression,” as does Andrei's entire life.

The battle is historically christened with the nickname “the sun of Austerlitz”, which Tolstoy does not mention though he describes why it is associated with that. Fog enshrouds the field in the morning, but the sun eventually burns through. By that time the French have already advanced further than the Russians are anticipating.

“It was nine o’clock in the morning. An unbroken sea of fog spread below, but at the village of Schlapanitz, on the heights, where Napoleon stood, surrounded by his marshals, it was perfectly light. Over him was the clear blue sky, and the enormous ball of the sun, like an enormous, hollow, crimson float, bobbed on the surface of the milky sea of fog. The whole French army, including Napoleon himself and his staff, not only were not on the far side of the streams and bottomland of the villages of Sokolnitz and Schlapanitz, where we intended to take up a position and begin the action, but were on the near side, so close to our troops that Napoleon with his naked eye could distinguish between our troops on horseback and on foot. Napoleon sat a little in front of his marshals on a small gray Arabian horse, in his dark blue greatcoat, the same in which he had made the Italian campaign. He peered silently at the hills, which seemed to rise up from the sea of fog, and over which Russian troops were moving in the distance, and he listened to the sounds of gunfire in the hollow. On his face, still lean at that time, not a muscle stirred; his glistening eyes were fixed motionlessly on one place. His conjectures turned out to be correct.” (pp. 272 – 273)

Napoleon's sudden attack is highly effective. The Russians are soon routed. Kutuzov is wounded in the cheek. Andrei rushes to his side but it is a superficial wound, Kutuzov says the real wound is seeing his army in retreat. In a heroic moment, Andrei takes the standard of a retreating battalion and rallies the men, initiating a counterattack against a French artillery battery. He is wounded in the process.

He falls on his back looking up at the open sky. This is repeating pattern in the novel. When Nikolai is wounded at the earlier skirmish and wakes up looking at the night sky, feeling alone and forgotten, not glorious as he expected. Rostov's younger brother will have a similar experience later in the novel. Andrei lays on the ground, staring at the gray clouds in the sky, “bleeding profusely.”

As he lays there, Napoleon and his entourage, happen by. Obviously, Andrei is behind enemy lines. The French withstood Andrei's counterattack and drove it back. Napoleon notices Andrei and calls him “a fine death” before realizing that he is still alive. The Emperor orders that he be tended to and his eyes meet Andrei's for a moment. Here Andrei finds himself in the company of his hero, Napoleon. And yet...

“Looking into Napoleon’s eyes, Prince Andrei thought about the insignificance of grandeur, about the insignificance of life, the meaning of which no one could understand, and about the still greater insignificance of death, the meaning of which no one among the living could understand or explain.” (page 293) It is with such confused and downtrodden sentiments that Volume/Book One of War and Peace comes to a close.

Comments