Concerning Điện Biên Phủ

Obviously, I'm going through a bit of a Dostoevsky obsession (see here, here and here, as examples). Over 2,000 pages of him gives me plenty to chew on. Nevertheless, I have read several other books on various topics simultaneously during the first half of the year. I started Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy by Max Hastings on my kindle app. Hastings is one of several British military historians that I really admire. Keegan, Beevor, Kershaw, all of these Brits have written wonderful military histories. I have a couple other books by Hasting, as well as each of the others.

About one-third of the way through Hastings I paused to read another new kindle acquisition specifically on the First Indochina War and the subsequent French defeat at Điện Biên Phủ. Throughout the later part of the last century this defeat became a cliché for military incompetence as Little Bighorn was in the late 19th century. Now we can add Biden's disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan to that ignominious list.

In a way, Điện Biên Phủ haunts me now. It was a major mistake by a liberal (though colonial) power. This mistake came near the height of liberalism, though the liberal tide went on for decades after that. Until now. Now we have Planet Trump and the conservative backlash to all those years of rampant global liberalism. In part, Điện Biên Phủ represents the beginning of Fukuyama's “end of history.” Điện Biên Phủ is the classic liberal symbol of military defeat. As, now, is Afghanistan. So, yeah, I'm feeling haunted here at the end of history and Điện Biên Phủ seems strangely relevant to me.

Over many years my fascination with the Vietnam War has grown wider, into the years (1948 – 1954) when the Vietminh (forerunners of the Vietcong) fought the French while America financed the war. I have an interest in how the Vietminh movement started and was sustained by Ho Chi Minh and others. By coincidence a new book just published covers Uncle Ho's side of the story against the French leading up to Điện Biên Phủ. I am attempting to buy more books on kindle these days as my remaining shelf space is almost nonexistent but I refuse to pay $19 for a glorified pdf. So I'll keep an eye on that one for a cheaper price somewhere down the road.

The modest Vietnam collection of my library predominantly pertains to America's involvement there, of course. But I have a few books that also deal with the preceding French experience. The best of them is the first 250 pages of Phillip B. Davidson's Vietnam at War, which offers a pro-American military perspective on both wars fought there and the time in between. I was hoping to expand upon this fine work and reading Hastings inspired me to delve a little deeper.

So, I purchased (at $0.99, a great deal) the kindle version of a book specifically on the French-Indochina War simply entitled Dien Bien Phu by Anthony Tucker-Jones. It is part of a larger series on the Cold War. If the rest of the series is as good as this book then it offers quite an extensive overview of this undeclared war between the Communist Bloc and the West during the 1950's – 1980's.

While Davidson's account is still the best I currently have, this new kindle book offers many details that I have not read anywhere before. For example, I was fascinated to learn that the French fortified zone at Điện Biên Phủ was a showcase of French military engineering. But, I am getting ahead of myself. I plan to review the Hastings book in detail when I get around to finish reading it. For now, I will include just a couple of quotes from that source as I approach the topic of Điện Biên Phủ.

Tucker-Jones augments what I read in the works of broader scope by Davidson and Hastings in explaining how the French became entangled in a war with the Vietnamese after World War Two, how the Vietnamese responded and ultimately defeated the French. I have never really understood why the French fought at Điện Biên Phủ to begin with, but Tucker-Jones explains it succinctly.

France had a global empire that pretty much fell apart when the Germans captured Paris in 1940. By the time the French helped the Allies win World War Two their former colonies in Indochina were taken over by the Japanese. With Japan's surrender the French regained their former colonies, but they did not control Indochina as they had previously. By now, Ho Chi Minh, among others, had formed a “nationalist” movement for an independent Vietnam. This soon morphed into a Communist movement, especially after the Communists won control of China in 1949.

The First Indochina War officially began around 1948 though bloody fighting occurred as early as 1946. Many of these early engagements were horrific in their intensity and in civilian deaths. Tenacious street fighting in the port of Haiphong in October and November 1946 caused in the French navy to bombard the city which resulted in 6,000 Vietnamese civilian deaths. This incident marked a tipping point. “There could be no turning back,” Tucker-Jones writes.

These early battles were fought with inferior weaponry. The French were busy supplying their presence in northern Africa and other regions of the world. In Indochina their forces had to make do with mostly pre-World War Two arms and equipment. The Vietminh had to work with only what they captured from the French and, before them, the Japanese. The savagery of these battles was simply brutal and this would only get worse as the the French modernized their forces and as Communist China began to supply Ho's soldiers. All the wars in Vietnam were of the most barbarous kind.

Generally speaking, the war played out much as the war with America did later. The French controlled the major towns and cities. The Communists controlled the jungles and mountains. The French initially limited their operations to roads and rivers where greater mobility and abundant supply were possible. The Vietnamese resorted to ambushes to pick the French off one outpost at a time.

The Vietnamese army was led by Võ Nguyên Giáp. He was resourceful, using meager supplies to maximum benefit with limited ambushes while building up reserves to launch more conventional counterattacks. But whenever his forces attempted conventional warfare, the French would beat them with superior firepower and air sorties that included the first widespread use of napalm.

Still, the bottom line remained the same from 1948 up to Điện Biên Phủ in 1954. The French were seen as colonialists, as rulers. There were some Vietnamese who benefited from this system and supported it, especially in the southern part of the country around the Mekong Delta. But the mass of peasants and educated Vietnamese, particularly in the northern region of Tonkin, supported Ho as either nationalist or Communist. Gradually nationalism and Communism became the same thing.

Tucker-Jones comments: “The French made little effort to counter the Vet Minh’s political campaign to garner popular support amongst the population. Their generals concluded wrongly that, over time, a combination of mobile operations and static defenses would defeat the revolutionaries’ guerrilla and conventional warfare tactics. They were to be proved wrong.” (Page 51)

In 1950, Giap's forces overran a series of French outposts near the Chinese border, securing their supply routes to China and allowing for a serious build-up of training and supplies including artillery. Soon the Vietminh military capability was vastly improved. In addition, these string of victories wrought over 6,000 French causalities and an enormous loss of equipment. The Vietminh captured more than 9,000 rifles, 900 machine guns and 950 trucks. French morale plummeted.

It was then that General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny arrived. His effective presence soon turned the fortunes of war and French morale rose as Giap was handed one defeat after another. Unfortunately for the French, de Lattre died of cancer in early 1952. His replacement, General Raoul Salan, implemented Operation Lorraine, France's largest operation of the war. But this was foiled by Giap who by now had several crack divisions to throw at the French, leaving a strategic stalemate in place. Salan was replaced by General Henri Navarre.

Giap did not allow the French time to recover after Lorraine. He immediately invaded neighboring Laos to widen the war. Tucker-Jones states this turned out to be a strategic stroke of genius. “Giap’s invasion of Laos was a very significant turning point in the war. Previously, the French had been able to largely confine the conflict to Tonkin, with them operating from Hanoi behind the security of the de Lattre Line.” (Page 121)

The widening war required a new strategy from Navarre. “Looking at his situation maps, Navarre understood that if his men could dominate the invasion routes into Laos, this would cut off the Viet Minh threatening Luang Prabang. This would either force Giap to fight or withdraw. The best place to block Giap was at Dien Bien Phu, known as Muong Than in T’ai, and the flat valley formed by the Nam Youm river in the T’ai mountains. The region, although dominated by the Viet Minh, was still supportive of the French. Also, the T’ai capital of Lai Chu north of Dien Bien Phu, although cut off, was held by French-officered local units.” (Page 125)

This is why the French decided to build a fortified zone in the middle of nowhere near the Laotian border. Initially, Navarre saw Điện Biên Phủ as a forward base where he could support scattered French garrisons in the mountainous region. But when the French became aware of Giap's attempted concentration at the zone the idea was hatched to lure Giap into an attack he could not win and then to crush him in the isolation of his overstretched forces. I had never realized that initially Điện Biên Phủ was seen by the French as a forward base, not as bait in a fortress, though this changed.

Hastings offers some insight into the French overconfidence. “The decision was made without much intelligence about the enemy’s whereabouts or intentions. Giap was always better informed than his French counterpart, partly through well-placed communists in Paris, whose first loyalty was to the Party rather than to the tricolore. Nonetheless, Navarre said afterward, 'We were absolutely convinced of our superiority in defensive fortified positions.'” (Page 45)

Further, “Dienbienphu was a relatively small battle, engaging on the colonialist side barely a division. Yet it assumed decisive moral significance, because it was launched as a French initiative, with the explicit purpose of bringing the Vietminh to battle, and was then lost by epic bungling. Navarre’s bosses in Paris were in those days almost as confused as was the general himself, being unwilling either to give up the struggle or to continue it. France’s committee of national defense concluded at a November meeting that the strategic objective was 'to oblige the enemy to recognize the impossibility of achieving a decisive military outcome.'” (Page 45)

“French intelligence, striving to monitor this fevered activity in the northwest, estimated that Giap could muster just twenty thousand porters, who could feed only a matching number of soldiers. In reality, however, the communists mobilized sixty thousand. Strengthened bicycles became a critical link in the supply chain, each bearing a load of 120 pounds, rising in emergencies to 200. Communist leaders inspired not only their fighters, but also the porters, to levels of physical effort and sacrifice that few Frenchmen or mercenaries proved capable of matching.” (Page 50)

The French intelligence was as bad as the American intelligence at the end in Afghanistan. Along with a poor strategic understanding, Tucker-Jones points out another primary weakness in the French plan. “France’s greatest failing was its complete lack of a strategic airlift capability and the weakness of its tactical airlift. The French never really generated the ability to support more than one operation at a time...” (Page 101) Davidson also points out that by moving the focal point of operations far away from France's air bases around Hanoi, the French, in effect, exacerbated the relative scarcity of their air assets (Page 213).

Tucker-Jones does an excellent job of simultaneously summarizing the strategic weakness of Điện Biên Phủ and the nature of French strategic thinking: “Initially, Operation Castor and the seizure of Dien Bien Phu as a base aéro-terrestre was intended to distract Giap from Lai Chu and so relieve the T’ai units ready for an evacuation with Operation Pollux. Once French paratroops had linked up with the T’ais they would use Dien Bien Phu as a ‘mooring point’ from which to attack the Viet Minh’s rear areas. This was a terrible gamble because Dien Bien Phu had no ground link with other French garrisons and was 275km by air from Hanoi.” (Page 124-125)

When the French saw Giap's attempted concentration at the zone they interpreted it as an opportunity. “Upon gaining intelligence on Giap’s movements, Navarre and Cogny began to reconsider their plans. It seemed that Dien Bien Phu might act as bait from where the French could crush the Viet Minh, or at least act as a diversion in anticipation of an attack on the Red River Delta. Also, the almost complete destruction of the T’ai units meant that the original plan to use it as a rallying point was now completely redundant. Dien Bien Phu went from a forward operating base to a fortified camp, defended by a series of armed positions in the same manner as Na San. By the end of the year, there were almost 5,000 French troops at Dien Bien Phu. (Page 132)

French confidence remained high and they soon turned Điện Biên Phủ into a showcase for the world through an orchestrated publicity campaign. “The initial success of Castor, in terms of securing the base, soon meant that Dien Bien Phu was welcoming high-ranking military and political tourists. These included generals Navarre, Cogny and Lauzin, and even the French defense minister René Pleven. Navarre and Gilles were photographed together at Điện Biên Phủ in December. They and the six officers behind them all looked in an ebullient mood. Foreign visitors included the British High Commissioner, Malcolm McDonald, and the British military attaché, General Spears. Among the Americans, was the U.S. army commander in the Pacific, General John ‘Iron Mike’ O’Daniels.” (Pp. 135 – 136)

Of course, by giving the fortified zone so much publicity the French also raised the value of the place in the eyes France and the world. France was drawing a line in the sand. This would be where the decisive battle would be fought. From the French perspective, Giap could not possibly move the substantial force necessary into the mountainous jungle region where there were no major roads. Even if they managed to mount a massive assault, the French fortifications were impregnable to the Vietminh offensive capability. This was the French perspective and they boasted it to the world.

Tucker-Jones describes the herculean effort the Vietminh mounted to respond to the fortress (actually several interlocking forts) at Điện Biên Phủ. “The Viet Minh hacked five routes through the jungle toward the French base. As well as tens of thousands of porters on foot and using bicycles to shift supplies, Giap’s men had 600 Russian-built 2.5-ton lorries, which traveled by night with their lights off to avoid attracting attention. Nonetheless, the weather and French air force together conspired to ensure that this build-up did not run smoothly. The torrential rains turned the valleys into marshes and many fords were impassable. French pilots attacked the Lung Lo and Phadin passes, resulting in sections of the roads sliding into the ravines below.” (Page 144)

The French harassment of Giap's logistics did not translated into an accurate assessment of the situation. The Vietnamese more than tripled French estimates in how many troops they could throw against Điện Biên Phủ. It was ultimately an overwhelming number of soldiers, used in numerous human wave attacks, some by night, accompanied by far more artillery than the French ever imagined that defeated France at Điện Biên Phủ. As I said, this is the most ignominious military defeat of the 20th century. The Vietminh won their independence (sort-of) with a victory over the great French bastion.

Tucker-Jones offers a lot of details about the defeat, fortress-by-fortress, over a campaign lasting a couple of months. This is a great accompaniment to the accounts of Hastings and Davidson. I feel that between these three sources (and a couple of other general histories) I have a fairly complete account of the French-Indochina War. I'm sure The Road to Dien Bien Phu will add a lot from the Communist perspective and I look forward to reading that one day when the price is right.

All this reading coincided with my purchase of a computer wargame. Campaign Series: Vietnam is the latest addition to my wargame library, which includes dozens of printed board games and computer games. As with my book library, I find myself running out of shelf space for all this stuff. For the first time in my life, I don't plan on buying very many other printed wargames. Just a few here and there, certainly. But (with one exception that I'll mention in a future post) there is nothing in print right now that I want to purchase and that has not been the case through most of life. I might actually favor the computer realm going forward. It does not require physical space.

Anyway, Điện Biên Phủ is explored through ten different scenarios in that computer game, which covers all of the First Indochina War, firefights during the time between wars, and the American involvement up through 1967. It is the latest evolution of this old John Tiller series that goes back to the 1990's. I've played those games forever, but not recently. These games have given me numerous hours of entertainment and military insight.

By coincidence, Campaign Series: Vietnam was just released in January of this year, so it is a brand new game. I have played a couple of the Điện Biên Phủ scenarios. It is a fun system. You can play either side against the computer or even let the computer play itself. It offers details into different weapons, units and tactics during the Vietnamese conflict. Actual game play is fast since the PC does most of the work. I am enjoying it.

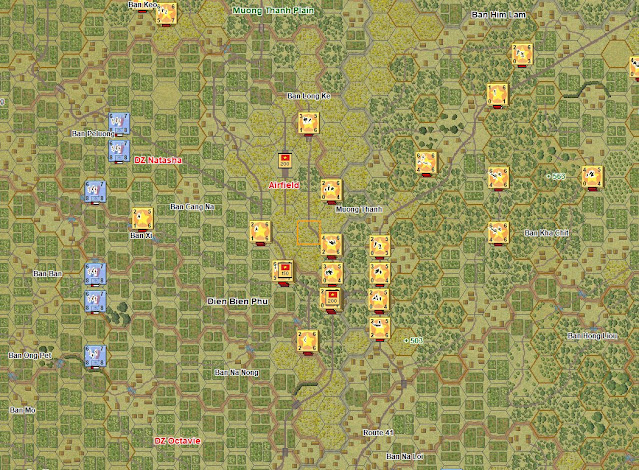

I like to play Vietnam games in the summertime. Fighting in the tropics feels right in the summer. Cold weather makes it seem weird and I'd rather be playing something on the Eastern Front of World War Two. What follows are a few screen shots of the fighting around Điện Biên Phủ in chronological order, as represented in the game Campaign Series: Vietnam. They are historically accurate, which adds to my understanding of this situation.

|

| March 14, 1954. The Vietminh attack and take the Gabrielle fort in a night attack (which is why the terrain is darker in this scenario). |

|

| Close-up of the night attack on Gabrielle. |

|

| March 30, 1954. The Vietminh throw a mass attack at the primary interlocking fortresses at Điện Biên Phủ. The French manage to repel this assault but their perimeter is shrinking. |

Comments